Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major public health challenge for Australia. Acute infection progresses to chronic disease in about 75% of cases, and these people are at risk of progressive liver fibrosis leading to cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). About 20%–30% of people with chronic HCV infection will develop cirrhosis, generally after 20–30 years of infection.

In Australia, the diagnosis of HCV infection has required mandatory notification since the early 1990s. HCV notifications by jurisdictions are forwarded to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, with recording of information including age, sex and year of diagnosis. Total HCV notifications and estimates of HCV incidence and prevalence in at-risk populations, particularly among people who inject drugs (PWID), indicate that a high proportion (80%) of people with HCV infection have been diagnosed. [1-3] At the end of 2020, it was estimated that there were 117 814 people in Australia living with chronic hepatitis C. [4]

The incidence of new HCV infections in Australia has declined since 2000, related to both a reduction in the prevalence of injecting drug use and improved harm reduction measures (eg, needle and syringe programs and opioid substitution treatment uptake) among PWID. The proportion of new HCV cases in young adults (aged 20–39 years) provides the best estimate of incident cases. Modelling suggests that the incidence of HCV infection peaked at 14 000 new infections in 1999 and had declined to 8500–9000 new infections in 2013.[1,3] There is some evidence of further declines in the incidence of HCV infection since the unrestricted availability of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy in 2016.[4]

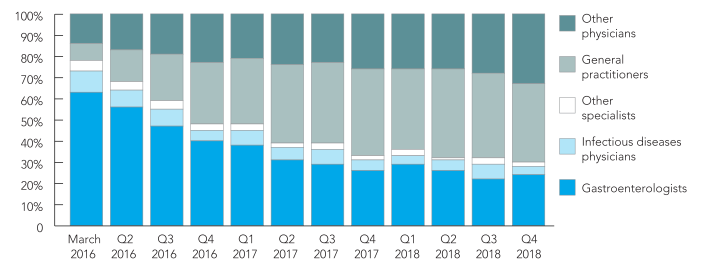

Despite one of the highest HCV diagnosis rates in the world, treatment uptake in Australia was low (2000–4000 people/year, or 1%–2% of the infected population) before the DAA era. In contrast, between March 2016, when interferon (IFN)-free DAA regimens were listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), and the end of 2020, a total of 88 790 people received HCV treatment (Figure 1).[5]

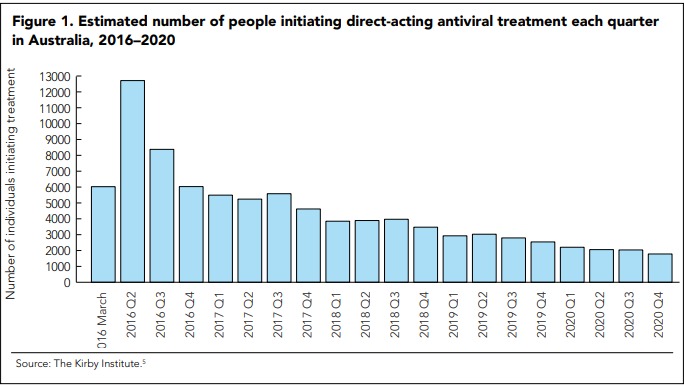

A key feature of the Australian HCV treatment landscape since the DAA program commenced has been the involvement of non-specialists in prescribing. Although the overall numbers of DAA treatment initiations per month have declined since March 2016, the contribution from general practitioners has increased (Figure 2). [6]

|

Figure 2. Quarterly distribution of prescriber types for people initiating direct-acting antiviral treatment, 2016–2018

Other physicians include supervised medical officers (e.g. interns, resident medical officers and registrars), public health physicians, temporary resident doctors, other/unclassified non-specialised and undefined. |

In addition to efforts that increase the number of people treated overall, strategies that target populations with high HCV transmission risk will be required to facilitate HCV elimination by preventing new infections (“treatment as prevention”).

Recent evidence from the Surveillance and Treatment of Prisoners with Hepatitis C (SToP-C) study in New South Wales prisons shows a halving of incidence after rapid upscaling of DAA therapy. [7] Encouragingly, among PWID in Australia, the estimated HCV antibody prevalence declined from 51% in 2016 to 39% in 2020, and the estimated prevalence of current HCV infection declined from 33% in 2016 to 16% in 2020. [8] Data also indicate that HCV treatment uptake in the DAA era has been higher among people with current drug dependency or injecting drug use than among those in the broader population of people with hepatitis C. [9]

Ongoing efforts will be required to sustain DAA treatment uptake, particularly among highly marginalised populations. Elimination programs in Australia should focus on increasing testing rates and linkage with care to maintain adequate levels of treatment.10 Enhanced DAA access in drug and alcohol services, community clinics and prison clinics will be needed for HCV to be eliminated as a major public health issue in Australia. [10]